As a child, Paula Day would creep downstairs to peer around the door of her parents’ studio at their house on Cheyne Walk. ‘It was very important and I wasn’t allowed to interrupt them,’ she recalls. Occasionally, her father Robin beckoned her to come in quietly, and he would sketch cartoons for her on his drawing board. ‘He told me that they were “world-famous designers” and I didn’t know what that meant, but I repeated it to everyone! That’s a child’s eye view,’ she says, laughing.

He may have been teasing his daughter, but there was truth to Day’s statement. When Robin and Clive Latimer won the Museum of Modern Art’s fêted Low-Cost Furniture Competition in 1948, the world sat up and paid attention. By 1951, Day and his textile-designer wife Lucienne were recognised as the stars of Britain’s burgeoning modernist-design movement.

The significance of that year cannot be overstated. The opening of the Royal Festival Hall, the Festival of Britain and the Days’ participation in the Triennale di Milano took their careers to a new level, as a shift in the cultural consciousness of the nation took place. A sense of hope and possibility, a determination to rebuild better after the horrors of the war, to give every citizen a stake in the future, took hold.

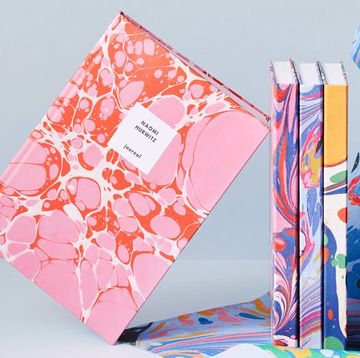

What's everyone reading?

The Days embodied that optimistic spirit with their designs. In fact, they were their own ideal customers: a young couple who set up home during the war, furnishing it with contemporary pieces that were affordable, compact and made in available materials. ‘They started out with very little money, but huge ambition and vision,’ says Paula.

The austerity of the war informed Robin Day’s pared-back aesthetic and resourceful ethos: both ahead of its time and timeless. ‘His modest family background meant he grew up taking it for granted that, if one was thrifty with things, and if you were creative, you could make good things with minimal resources. He hated waste; he knew things had to be economical, functional and meet real human needs. His outlook is relevant today, in the face of the climate crisis. He felt passionately about those things,’ Paula says.

Through the Robin and Lucienne Day Foundation – established in 2012 – Paula partners with carefully selected licensees on editions of her parents’ work. Case Furniture reissued Robin’s ‘Forum’ sofa and armchair, designed in 1964. A cherished part of Paula’s childhood (there were two ‘Forums’ in the Day’s Chelsea home), its construction, with the hardwood-and-chrome frame proudly visible, rather than concealed beneath the upholstery, make it a mid-century classic.

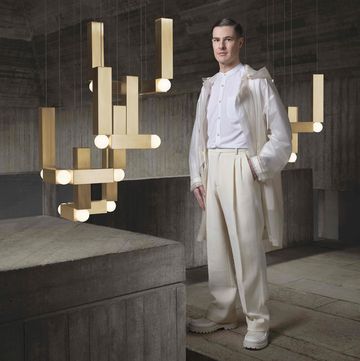

More of Robin Day’s ingenious designs are now being released in a collaboration between the foundation and Danish brand &Tradition. The range includes the ‘Daystak’ desk and side chair, and the ‘RFH’ designs – five pieces that Day created in 1951 for the Royal Festival Hall, described by Paula as ‘so imaginative, so joyous’ – that are available to purchase for the first time.

Paula wanted to partner with companies skilled in producing historic furniture with a global reach. After meeting &Tradition founder Martin Kornbek Hansen in 2020, she knew it was a perfect match. ‘There have been challenges, but they’ve been resolved very successfully,’ she says of the project, which took four years to realise.

Those issues include the changing proportions of the human form. ‘People are bigger now than in the postwar period, so it’s common for designs to be scaled up slightly,’ she explains. ‘If you make the chair legs taller, you change the proportion of the design. If you make a seat bigger, the plywood is more flexible; you may have to thicken it, which affects the aesthetic.’

The ‘Daystak’ chair was scaled up in size by two per cent – enough to satisfy contemporary needs – while the terrace furniture designed for the Royal Festival Hall has been reimagined in a high-quality plastic laminate, as a more sustainable and durable alternative to tropical hardwood.

In a 1962 magazine interview, Robin said ‘A good design must fulfil its purpose well, be soundly constructed, and should express in its design this purpose and construction,’ recalling the principles of the Arts and Crafts movement. Paula agrees his work is innately English: ‘It is radical but in an understated way. He was allergic to showiness! Reserve is very true of my father’s work, which doesn’t lessen its originality or its power.’

Modest but possessed of unshakeable self belief, the Days were driven to create things to improve people’s everyday lives. ‘That took real strength,’ asserts Paula. ‘As unknowns, both had the opportunity to be in-house designers, but they stayed freelance and were not prepared to compromise. My father did a lot of public seating, and he found it satisfying because it was made for everyone. You don’t have to buy it, you just sit on the “Toro” bench on the Tube. That’s the ultimate in furniture that meets people’s needs.’ As Robin’s work is poised to reach a new audience, it’s clear the Days’ belief in the democratic power of design could not be more relevant or necessary today.